Publication Date:

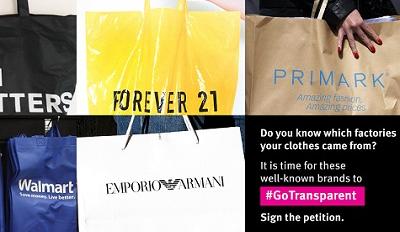

The garment and footwear industry stretches around the world. Clothes and shoes sold in stores in the US, Canada, Europe, and other parts of the world typically travel across the globe. They are cut and stitched in factories in Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, or other regions. Factory workers in Bangladesh or Romania could have made clothes only weeks ago that consumers elsewhere are eagerly picking up. When global supply chains are opaque, consumers often lack meaningful information about where their apparel was made. A T-shirt label might say “Made in China,” but in which of the country’s thousands of factories was this garment made? And under what conditions for workers?

There is a growing trend of global apparel companies adopting supply chain transparency—starting with publishing the names, addresses, and other important information about factories manufacturing their branded products. Such transparency is a powerful tool for promoting corporate accountability for garment workers’ rights in global supply chains. Transparency can ensure identification of global apparel companies whose branded products are made in factories where bosses abuse workers’ rights. Garment workers, unions, and nongovernmental organizations can call on these apparel companies to take steps to ensure that abuses stop and workers get remedies.

Publishing supply chain information builds the trust of workers, consumers, labor advocates, and investors, and sends a strong message that the apparel company does not fear being held accountable when labor rights abuses are found in its supply chain. It makes a company’s assertion that it is concerned about labor practices in its supplier factories more credible. The need for information about factories involved in production for global brands has become painfully clear in recent years through deadly incidents that have plagued the garment industry.

The Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh on April 24, 2013 killed over 1,100 garment workers and injured more than 2,000. In the year before the collapse, two factory fires—one in Pakistan’s Ali Enterprises factory and another in Bangladesh’s Tazreen Fashions factory—killed more than 350 workers and left many others with serious disabilities. These were the deadliest garment factory fires in nearly a century. Until these tragedies occurred, virtually no public information was available concerning apparel companies that were sourcing from the factories involved. The only way to identify these apparel companies and advocate for accountability was to interview survivors and rummage through the rubble afterward to find brand labels. A system of corporate accountability that requires people to scramble on the ground for brand labels is the antithesis of “transparency.”

Over the past decade, a growing number of global apparel companies have published information on their websites about factories that manufacture their branded products. For more than a decade, adidas, Levi Strauss, Nike, Patagonia, and Puma have been publishing information on their supplier factories. Over time, more apparel companies and retailers with own-brand products joined them, posting some information about supplier factories on their websites.

As more companies adopt supply chain transparency, it is becoming a cornerstone of responsible business conduct in the garment sector. Increasingly, brands and retail chains are beginning to understand that being an ethical business requires them to publish where their own-brand clothes or footwear are being made.

Publication Type:

- Report